Paula Rego, Dog Woman, 1994 Pastel on canvas, 120 x 160 cm © Paula Rego; courtesy Marlborough Fine Art

Paula Rego: The House of Stories

by Deanna Sirlin

In February of 2020, I had the pleasure of visiting a museum in Cascais, Portugal devoted to the work of the artist Paula Rego (b. 1935) and that of her spouse, artist Victor Willing (1928 – 1988). The museum, which opened in 2008, is called Casa das Histórias' (the House of Stories). It was designed by architect Eduardo Souto de Moura, who was chosen by Rego herself, rather than through an open competition. The architecture has a strong presence dominated by two pyramid-like forms. The museum, built of colored concrete in an intense hue of terracotta, is powerfully elegant and sensitive to the site. When you approach this building, you experience its relationship to the landscape as that of a work of modernist sculpture.

Casa das Histórias' has a permanent collection of Rego’s etchings (257) and drawings (278). Rego has loaned 52 paintings to the foundation. The exhibition currently on view through May 24, 2020, Paula Rego: Writing Drawings, Staging Stories, does exactly that; it presents Rego as a storyteller. The page or canvas becomes a kind of proscenium within which her figures act out dramas that stem from her love of fairytales mixed with a surrealist sensibility that endures from her early work of biomorphic forms inspired by Miró and Gorky.

Casa das Histórias Paula Rego in Cascais, Portugal, Eduardo Souto de Moura, architect. photo: Deanna Sirlin

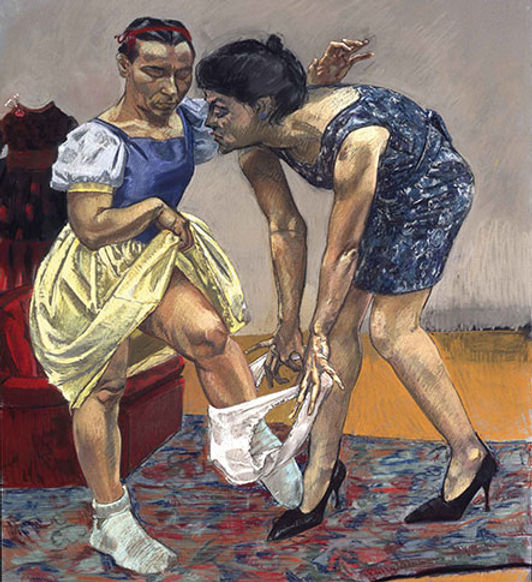

Rego is enamored by the darkness of fairytales. She reinvents them as personal nightmares with overtones of fear in new versions that are even scarier than the original tellings. Rego produced a series of drawing and prints based on Disneyesque images of Snow White, Pinocchio, and Peter Pan as well as images from Jane Eyre. Rego shifts the hierarchy in the stories, recontextualizes them into contemporary life, and fills them with a kind of sexual dread. Snow White and her Stepmother, a large pastel from 1995, is a disturbing and loaded image of her model Lila Nunes (who is a stand-in for the artist but also plays “many other roles” in her work, according to Rego) wearing garb that we recognize as the dress of Snow White and being helped by an older woman in a tight dress and black stilettos to step into a large pair of white underwear. There is something ominous in this act between the two women: Snow White, the unhappy child, being forced into (or perhaps out of) her underwear. The power of the work lies in the creepiness of the content combined with the powerful form of the figures.

Paula Rego, Snow White and her Stepmother, 1995. Pastel on paper mounted on aluminium, 178 x 150 cm Courtesy of The Whitworth, The University of Manchester. © Paula Rego

The current exhibition features many of Rego’s personal studies in ink on paper. These small drawings have the power of Goya, with an elegant fluidity of line. Study for History II, 1986, one of a series of drawings, shows a dog trying to advance sexually on a rabbit as she tries to fend him off. In the same room, there is another series of drawings from 1986 titled Girl and Dog, in which Rego’s brushed ink lines depict a kind of power play between these characters, with the viewer as witness. A wide array of different types of beings interact with one another in this exhibition, the artist depicting their roles in these very direct sketches. Included in this exhibition are a series of fabric sculptures that Rego constructed as models for her paintings. While dolls can be spooky, these are so bizarre they feel a bit like they were made in a grotesque dream. Among these sculptures you find The Seven Deadly Sins and The Sea Nymph; the spookiest is The Muses Tree, a tall figure hung with plants and dildo like forms. There is also a large triptych drawing, Human Cargo 2008, which takes on human trafficking. Rego is not afraid to tackle uncomfortable subject matter—in fact, she faces it head on.

Paula Rego, Study for History II, 1986, Indian ink on paper 29 x 38 cm Collection Câmara Municipal de Cascais, Fundação D. Luís, Casa das Histórias © Paula Rego

Straightforwardness and authority characterize Rego’s work from the very beginning of her career. Rego studied at the Slade School of Fine Art in London. Dog Woman, 1952 is a small drawing Rego made when she was still in school there. A powerful work, the marks created by the anger of oppression, this figure exudes the feeling of the frustration of being a woman who “always did as she was told.” She is down on the ground lashing out. Rego made another Dog Woman in 1994, drawn in a completely different manner but filled with the same anger, the mouth open in an expression of vocalization. Here the drawing is in full color using pastels, the form much more defined in a realistic manner. The intensity of hues that Rego achieves using pastels evokes Degas, but the way the figure is so stunningly articulated, each muscle pronounced, calls up the work of the artist Lucian Freud, who was a visiting tutor during Rego’s time as a student at the Slade. Rego relayed to me , “Lucian didn’t study at the Slade. He came in as a visiting lecturer. I think he was looking for girlfriends. He didn’t talk at all he just looked. He said he taught by telepathy. Vic [Victor Willing, Rego’s spouse] knew him better as they were both friends of Francis Bacon’s. Vic wrote that Lucien was ‘beautiful as a knife’, luckily Lucien never took an interest in me. I admired his work very much, I admired his precision.” The physicality Rego achieves through light and color, the directness of the figure as it is realized through her mark-making, and the virtuosity of the image lend the work enormous intensity.

Paula Rego, Dog Woman, 1952, Pencil on paper, 15,5 x 21,5 cm Collection, Casa das Histórias © Paula Rego

“To be a dog woman is not necessarily to be downtrodden; that has very little to do with it,” Rego explained. “In these pictures, every woman's a dog woman, not downtrodden, but powerful. To be bestial is good. It's physical. Eating, snarling, all activities to do with sensation are positive. To picture a woman as a dog is utterly believable."

Rego understands only too well her place as a female in society and in the studio. She described herself growing up in Portugal, where as a woman of her class she did nothing, and working class women did “everything.” She was commissioned to paint the author Germaine Greer, considered to be a major voice of second wave feminism. The portrait, which is in the National Gallery (UK), shows Greer sitting on a low black couch. Greer is wearing a red dress with her legs spread and the soles of her shoes touching. Greer’s hands are centered on her body; she is making a circular opening with the joining of her hands directly in front of her pelvis. Her head is titled in a listening or thinking pose.

For me, the sitter is so present I was surprised to read in interviews with both Greer and Rego that making the painting was a difficult process. However, the force of this portrait might reside in the struggle to capture the sitter and portray her power and intellect.

Paula Rego, Germaine Greer, 1995 pastel on paper laid on aluminium, 47 1/4 in. x 43 3/4 inches National Portrait Gallery © Paula Rego

Paula Rego, Dancing Ostriches, 1995, Pastel on paper mounted on aluminium 150 x 150 cm image: Saatchi Gallery © Paula Rego

Rego’s work that involves the female figure is fabulously in-your-face about concepts of feminine beauty. She takes on the notion of what is beautiful in her series of “Dancing Ostriches,” in pastel on paper mounted on aluminum in a square format, which mocks the very notion of lithe anorexic ballerinas. Her dancers wear black tutus that reveal large breasts and muscles, and light pink toe shoes, their large bodies stretched across black leather sofas. Their muscles are articulated by the light that emphasizes the physical structure of the model, Lila Nunes, who was originally the caretaker for Rego’s husband, Victor Welling, and stayed on as her model and surrogate self. It may seem strange that she chose Nunes as a surrogate for herself as they are opposite physical types, but perhaps Nunes exemplifies the strength of Portuguese women for Rego. Rego says,“She can play many roles and does in my work.”

In 1998, there was a referendum to decriminalize abortion in Portugal, which failed by less than two percent. In response to this vote, Rego made a series of pastels of women undergoing illegal abortions. These young women sit on couches, their legs spread with buckets nearby to hold the medical waste. This harsh depiction of the backroom abortion has such power that when a new referendum came up to legalize abortion in Portugal in 2007, these pictures were credited with its passing. I know of no other artist who has taken a strong political stand in their work and succeeded in changing public opinion since Picasso’s Guernica, the anti-war painting whose exhibition in Europe helped raise money for refugees from the Spanish Civil War.

Paula Rego, Untitled n. 5 (1998–1999). Pastel on paper mounted on aluminium, 110 x 100 cm

Photograph courtesy of Marlborough Fine Art, all rights reserved. © Paula Rego

Prior to visiting Portugal, I had only seen a few works by Paula Rego, and I ask myself why is this the case. Rego was awarded the Medalha de Mérito Cultural, the most prestigious cultural award in Portugal. At 85, her life as an artist has been a slow and steady version of “nevertheless she persisted.” Having studied and lived in London, but always returning to her native Portugal to visit and for exhibitions of her work, she is considered one of Portugal’s most important living artists. In 2004, her retrospective at the Serralves Foundation in Porto was open 24 hours a day with tours in the middle of the night because it was so popular. Currently, there is a large exhibition of her work traveling around the UK. This exhibition, Obedience and Defiance, premiered at the MK Gallery in Milton Keyes, and then traveled to Scottish National of Art and will open at the Irish Museum of Modern Art In Dublin On June 12, 2020. The Tate Britain will have a full-scale retrospective of her work in 2021. This exhibition was instigated by the National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA) in their promotion of #5womenartists.

Rego is very well known in the UK and Europe where she has had no shortage of major museum exhibitions in Europe. She has even made inroads into the US: in 2008 Rego had a major exhibition at NMWA in Washington, DC which had traveled from the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid, where it was shown in 2007. She is represented in major American collections. The Metropolitan Museum of Art has two of her lithographs in its collection, neither of which is currently on view. MOMA owns one etching with aquatint that can only be seen online.

Paula Rego courtesy Facebook.

But why is Rego, clearly a world-class artist and a powerful feminist voice, not better known in the US? I would prefer not to believe it is because she is a woman, though that certainly is part of it. I was interested to see that the entry for "School of London" on the Tate’s website listing art terms mentions only male artists and excludes Rego, despite her connections to it through the Slade and the clear stylistic affinities her work shares with other members of the group. I suspect that if you ask most people in the US to name a woman artist, they will say Georgia O’Keefe. In Germany, Paula Modersohn-Becker is so well known they call her Paula – no surname necessary, the same way we in North America say Frida for Frida Kahlo. However, O’Keefe, Modersohn-Becker, and Kahlo are all from the 20th Century, the past. We have a new Paula for the trying times of the 21st Century who is an art warrior for the strength of women everywhere.

Paula Rego: Writing Drawings, Staging Stories

Casa das Histórias Paula Rego, Cascais, Portugal

December 5 - May 24, 2020

For a 3D visit to the exhibition click here

Deanna Sirlin is an artist and writer from Brooklyn, New York currently living and working outside of Atlanta, Georgia.

Sirlin is Editor-in-Chief of The Art Section.