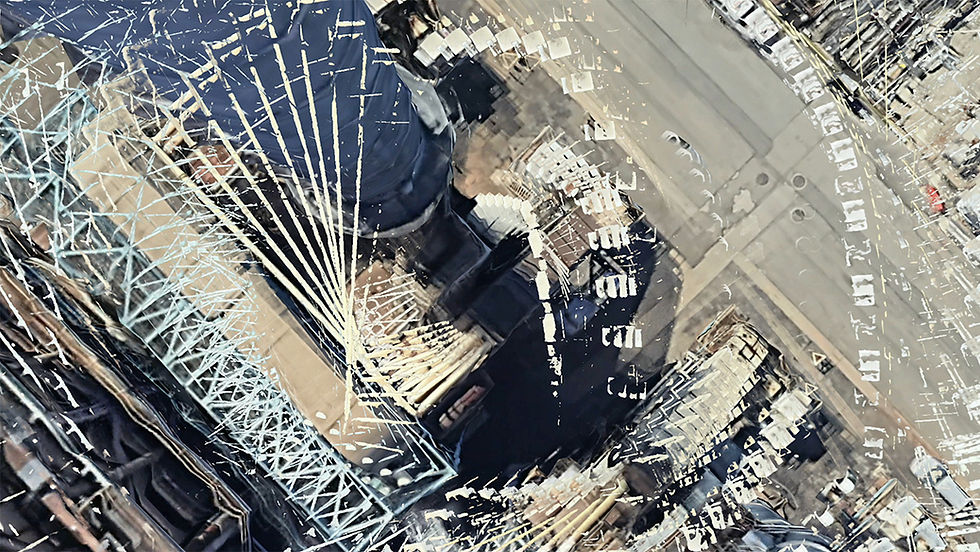

Video still from Pulse,2023, Courtesy of Debora & Jason Bernagozzi

Pulse, 2023, Single Channel Video/Live Performance, Live Video Processing by Debora Bernagozzi, Custom Software (SC Frame Buffer), Sound by Jason Bernagozzi

Courtesy of Debora & Jason Bernagozzi

Signal Culture, founded by Jason Bernagozzi, Debora Bernagozzi, and Hank Rudolph in 2012, takes its place in the history of organizations devoted to the support and development of media art. Although the term “media art” first gained popularity in the age of the internet, the idea of making work in a fine art context using media technologies has a much longer history. While video art is the form primarily associated with the development and life of media art, the first such experiments arguably took place in the realm of music, where compositions using pure electronic sound first appeared in the 1950s. These were preceded by experiments in using sound recording and editing techniques to produce music that could exist only as recordings (sometimes called “tape music”) as early as the 1920s. Media art developed in tandem with technology: the arrival of consumer-level tape recorders after World War II; Robert Moog’s development of his keyboard-based synthesizer in 1964; and the advent of the Sony Portapak, a portable video camera and recorder, in 1965 were all watershed moments when means of producing media art were placed within reach of visual and sound artists interested in experimenting with them.

Organizations arose to foster and facilitate media art practices and to create communities around them. The San Francisco Tape Music Center in San Francisco, founded in 1962, and the Center of the Creative and Performing Arts at the State University of New York at Buffalo, which opened in 1964, were among the earliest and most important in music. Video art hit its stride in the early 1970s. Several of the organizations dedicated to its development were allied with public television stations, such as the National Center for Experiments in Television at KQED in San Francisco, founded in 1969, and the New Television Workshop, which began at WGBH in Boston in 1974. Outside of broadcasting, one of the most important organizations promoting video art was the Experimental Television Center (ETC) founded by Ralph Hocking in Binghamton, New York, in 1971. All of these organizations existed to provide artists with access to the equipment they needed to create new media work, time to develop their own work and present it, and opportunities for dialogue and collaboration with like-minded artists and technologists.

Signal Culture continues the legacy of the upstate New York media arts community, particularly Ralph Hocking and Sherry Miller Hocking of ETC, by serving as a support system for artistic creation through the development and dissemination of technological tools for use by artists, residencies for artists and tool-makers to work side-by-side, and exhibition opportunities.

In addition to their work with Signal Culture, Debora and Jason Bernagozzi are artists who work individually and collaboratively in a range of forms that includes video installations and performances. Jason Bernagozzi’s installations often focus on landscape and the history of specific places, merging and distorting images through various techniques of signal processing and digital manipulation. Debora Bernagozzi is a photographer and video artist who is exploring the possibilities of bringing together the traditional craft of lace-making with video. The Bernagozzis’ live performances entail the manipulation in real time of found and created images and sound, sometimes recognizable and referential, at other times purely synthetic, using custom-made software and digital tools developed at Signal Culture.

Philip Auslander

Atlanta 2024

Jason Bernagozzi, Diachrony, 2021 (Excerpt), Courtesy Jason Bernagozzi

Philip Auslander: Signal Culture is a not-for-profit organization founded over 10 years ago in order to support experimental media art through residencies, exhibitions, and the development of applications. How did this venture come into being? What needs did you and the other founders see that you wanted to address?

Debora Bernagozzi: Jason and I had both participated in artist residencies through the Experimental Television Center (ETC), Squeaky Wheel, and the Kuala Lumpur Film and Video Festival that had been transformative for us both personally and artistically. We had dreamed of creating that kind of opportunity for others. When ETC closed its residency program, it left a real hole in the community which no longer had a place that was dedicated to real time experimental media art.

Jason Bernagozzi: During that time, we were also concerned about what seemed like a divide between artists, researchers (curators, theorists, etc.) and toolmakers (engineers, programmers, hackers). A common thing you would hear from artists is that you can’t trust writers to accurately represent your practice, especially when they argue that to “focus too much” on the technology is non-conceptual. Additionally, there were moments where writers would tell me that they didn’t want to meet artists from a particular practice they were researching because “the artists have too much of an opinion about their own work.” As people who strongly believe in the potential of community, we wanted to create an environment where these divisive preconceptions could be mended.

DB: We were inspired, in part, by Dave Jones, a self-taught video engineer whose hardware and software has been an integral part of the studios at ETC and Signal Culture, but who has also been a part of the creation of some of the best-known video art, especially in his toolmaking for Gary Hill. We would hear stories from Dave and others of the “Tuesday Afternoon Club,” an informal gathering of video artists who lived in central New York state in the ‘80s and would come to his house to make video instruments together.

JB: Inspired by this, we wanted to make sure our residency program supported not only artists, but also researchers and toolmakers working in the field. So, when we set out to find a space to set up, we made sure that we could have simultaneous residencies going at once, where we could have an artist and also a researcher or toolmaker for every residency period. By having the residencies happening concurrently, participants can exchange ideas (or sometimes have spontaneous collaboration), and we can inspire empathy and a sense of community that respects the foundational work that goes into the ecosystem that supports it.

Video still from Pulse, 2023, Courtesy of Debora & Jason Bernagozzi

DB: When we came up with the idea for Signal Culture, we quickly invited Hank Rudolph to be the other co-founder. Hank had been the Residency Director for ETC for decades, maintaining the studio and training residents on equipment. Hank is one of the most knowledgeable people about the kind of studio we wanted to create and one of our closest friends, so he was a natural collaborator.

Signal Culture has welcomed over 400 artists, researchers, and toolmakers from close to 30 countries for residencies so far. We’ve curated exhibitions and screenings, primarily of alumni work. We’ve also focused on the resources part of our mission, editing two Signal Culture Cookbooks, e-books focused on the creation of experimental media art or tools and creating a suite of Signal Culture Apps that people can use to create their own art.

PA: How do you define “media art”? What is the relationship of this term to some of its predecessors, such as expanded cinema, experimental television, etc.?

DB: While most of our artists are working in real-time experimental video, we used “media art” to broaden the possibilities for both current and potential future practices that we might support.

JB: Historically, expanded cinema and experimental television were certainly both central to the emerging ideas and practices of that time, but I would say that electronic music and experimental aleatoric composers had an equally important role in that they were searching for possibilities and not focusing on a consumable product. As [pioneering video artist] Woody Vasulka once said, you “have to share the creative process with the machine. It is responsible for too many elements in this work.” The relationship with the technology is a dialogue: as you change it, it also changes you. So, in the case of working with video synthesizers, imagine instead of coming to a machine with the goal of executing visual “effect,” these real-time machines can be conceived of as instruments or extensions of the body. They embody process, not an end point.

DB: To answer your question of a definition more directly, though, “media art” definitions vary, but all include the use of technology in artmaking. We like that the definitions encompass lots of ways of making, and we’ve had folks working with experimental sound, live coding, lasers, 3D scanning and printing, digital printmaking, VR, and more. We love the possibility that this broad definition welcomes.

Video still from Ritual for Synthetic Media, 2023, Courtesy of Debora & Jason Bernagozzi

PA: What are the relationships of media art to more traditional forms such as painting, photography, music/sound art, and performance?

JB: I think it isn’t medium specific, it is more about a mode of making using technologies, experimentally minded, and open in structure. We have had people classically trained in painting, printmaking, sculpture, and music come to our residency with fantastic results. I think a big misconception is that you must have a deep relationship with technology in order to pull some interesting ideas from it. One of our alumni, Kendall Harbin, is really a social practice/relational aesthetics-oriented artist who wanted to come not to produce video works, but to learn from the system to expand their social and linguistic vocabularies for their practice. We thought this was just a fantastic idea, and embodies what this way of working does to dissolve the boundaries between mediums.

DB: We embrace many ways of working with our studio. While some artists leave with footage that will become pieces to be screened in film and video festivals, others work very differently. Scott Kildall captured signals from a variety of video cameras, including the Sony Portapak, one of the first “portable” video cameras, to output as data to then 3D print. We’ve had artists capture video to make still images for digital prints, or to burn woodblocks to make traditional prints, or to use as sources for paintings.

Our toolmakers and researchers also work across many disciplines, including vector synthesis, repurposing video game controllers for artmaking, studying GIFs as communication, doing preservation research, and coding as both art in itself and coding to create tools for artmaking.

The history of video art is certainly intertwined with that of performance art. Thanks to the Sony Portapak I mentioned before, which was introduced in 1965, performance artists could watch what they were doing in real time on a monitor or projector and respond to that instead of recording a performance on film and waiting for it to be processed as a motion picture or photograph. Joan Jonas’ Organic Honey’s Vertical Roll (1972), where she physically performs with sound and her body in response to the vertical roll of an improperly synced television monitor, is an early example of this. Steina Vasulka’s Violin Power (1970-78), in which by playing the violin, she triggers live processing of video of herself is another iconic example.

There is a strong relationship between experimental electronic music/sound and experimental video since both are electronic mediums that use synthesizers and triggers and are open to improvisational approaches. We use oscillators frequently in our studio. The waveforms produced could create sound, be transformed into video, create keys or masks for combining videos, or trigger events like switches or fades.

Debora & Jason Bernagozzi, Ritual for Biological Media, 2019

A video and sound performance that investigates and meditates on the unseen world of biological processes as a metaphor for the transmission of data structures that govern our world.

Jason Bernagozzi is an artist whose work examines and critiques the codes embedded within the psyche of media culture. Bernagozzi’s work has shown at venues such as at the European Media Art Festivalin Osnabruk, Germany; the Festival Les Instants Vidéo Numériques et Poétiques in Marsaille, and the Ilman Museum of Art in Seoul, South Korea. Jason is a co-founder of the experimental media art non-profit organization Signal Culture and is an Associate Professor of Electronic Art at Colorado State University.

Debora Bernagozzi is an artist and curator in Loveland, Colorado. Her work has been exhibited in the US and internationally, including at the Denver Art Museum, Burchfield Penney Museum, Ann Arbor Film Festival, and the Kuala Lumpur Experimental Film and Video Festival. Her creative process is experiential, with video as well as with documentary photography and fiber art, including lacemaking. She serves as Executive Director of Signal Culture while continuing to make and exhibit her own work.

Debora and Jason Bernagozzi at Signal Culture

Philip Auslander photo: Marie Thomas

Philip Auslander writes frequently on performance, music, and art. His most recent books are In Concert: Performing Musical Persona, published in 2021, the third edition of Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture, and Women Rock! Portraits in Popular Music, both 2023. Dr. Auslander is a Professor in the School of Literature, Media, and Communication at Georgia Tech, and the Editor of The Art Section.