Michi Meko, Maulakins: And We Looked out unto it, 2018 Mixed Media 144" x 168"

Michi Meko

with Cinqué Hicks

Atlanta-based artist Michi Meko has all but stopped making art. Sort of. Since the onset of the pandemic, Meko has taken a deliberate refuge from the art world and from urban civilization in general. He hasn’t precisely gone into hiding, but he has sought to engage his artistic practice and think about artistic creation in ways that don’t include painting, studios, museums, or pretty much any of the what we think of as the infrastructure of art. Instead, Meko has been relearning what art making looks like when it’s divorced from production. Can prolific art making be a form of bondage in itself? In this dialogue, I speak with Meko about the new directions in his work and about disengagement as an artistic practice, as a source of radical creativity.

Michi Meko, Coded Message To Escape, 2018 , Mixed Media 72" x 86"

Cinqué Hicks: Tell me a little bit about what your practice looks like right now, in terms of themes that you're thinking about, techniques that you're thinking about, and that sort of thing.

Michi Meko: Right now, since this whole sort of pandemic, I really just sort of... I wouldn't say closed my practice, but I just felt the need to sort of sit and process like more than I’ve ever been able to before with work. So, I've taken on sort of a meditative practice of tying fishing flies. I'm trying to tie 400 of these flies right now and teach myself this whole thing and go through this sort of process.

As far as the painted work, I've only worked on two painted works since I guess the time of the pandemic. I'm really sort of going slow and thinking about what it is I'm trying to say and what it is I'm trying to make and why.

Michi Meko, Codes (detail)

CH: One of the things that I thought of when the pandemic started was that for all the awful effects of it, it does give a lot of us—if we're lucky enough—it gives us the gift of time. It slowed a lot of things down. Are you sensing that?

MM: Yeah. That was the thing that interested me most about it because I had been wanting a break and trying to find that break. I was doing exhibitions and I still work a day job and you have auxiliary responsibilities but sort of the world stops. It allowed me, in a very weird way, to get that break. I began to think about what leisure looks like, surprisingly, and what it looks like when people say mental health or when people say these sort of catch phrases like “self-care.”

I was having some issues of my own anxiety and panic attacks, so I was already sort of fitting in that space and then when the pandemic happened and then the isolation came, I was already prepared for that mentally. And so it just became a thing for me to say, “What is it that Michi really wants to accomplish out of this life or what do I want to accomplish out of this career? What have I accomplished?”

My main thing, right now, has been in pursuit of this project that I began thinking about in 2017, which was being Black in wilderness spaces and what the great outdoors means to Black bodies and what outdoor spaces, or public land means to Black people. Even like something as simple as a national park. I just loaded my car up and began to think about it as a bubble that can transport me to any of these spaces where I could have these thoughts, write these notes and do these drawings in these wilderness spaces and that's kind of what I been doing. Lots of camping and fishing.

Michi Meko, Maiden Voyage: Big Black - Panama City Beach 2016 Cast Iron Skillet, Nylon

CH: That goes back to the 400 fishing flies.

MM: Yes. That was sort of a way to slow down honestly, and not just go through the motions of making paintings for an exhibition—like: this exhibition, that exhibition, this exhibition, that exhibition. You gotta do this group show or that group show. The pandemic cut all that out and then people were calling for virtual studio visits and all of this, and I was just like "No, I'm not doing any of it." I just turned my back on the actual making of paintings or drawings and shifted the energy somewhere else into things that I was interested in.

Michi Meko, The Romantic: Summer 2019 Mixed Media 120"x 144"

CH: You mentioned going slow and figuring out why you're making these things. Have you arrived at any interim answers to that or any provisional thoughts? Or permanent ones?

MM: Well, right now I'm still asking the questions. What is the purpose, what is the rush to obtain this sort of wealth and fame or whatever it is that you want from art? Is it in pursuit of history books, or is it in pursuit of pure human expression? Do you want to leave a mark on the world? Or is it to say that I was here, I existed, culture existed? This is what people were doing where I existed at that time. I’ve been thinking about it like that, and what is the voice of the Black Americans like right now?

Michi Meko, We Leaving Now. 2017 Iron Create, Wood, Lantern, Doily

CH: You know, I keep thinking of Tricia Hersey's Nap Ministry. Are you familiar with that? She is a poet here in Atlanta. She has this very interesting practice called the Nap Ministry. It's all about how napping is a kind of luxury that has traditionally never been afforded to African-Americans, and particularly African-American women who have always had to work and be compelled to constantly go, go, go and just the luxury of being able to rest and take a nap is itself a revolutionary act. She stages these public nappings, where some people will just go to sleep. I don't know if she's done any lately, but I know that that was her practice for a while and as I hear you talk about the luxury of leisure, it takes on a kind of—“revolutionary” might be kind of a dramatic word—but there's a resistance there. Resistance to the hustle, resistance to constant, constant movement.

MM: Yeah. I have not engaged, I have purposefully disengaged and there was some overall guilt there, which is something I want to figure out, too. When all the riots happened, I just refused to engage. I didn't have the mental capacity to let myself go in these directions, which I was already dealing with, like these anxieties and all of these things. I really have disengaged.

I've taken that as a revolutionary act. I have several notes that I've been writing where I'm talking about this guilt. Then also feeling in some way privileged, that I have a car and that I have the time now, and the luxury to just run to the North Georgia mountains or run to the North Carolina mountains, or run to the Smokies and spend a weekend doing nothing and then the equipment that it takes to even do that, started to feel like a privilege and a luxury. Now, there are these great conversations around Black people and wilderness spaces and "blackening" or getting people of color involved in outdoor spaces. I'm very interested in what that looks like for myself.

Michi Meko, White Emotions 2017 Crawfish Baskets, Raw Hand Picked Stolen Cotton, Rope Doily

CH: I think one of things that's interesting about what I'll call this "George Floyd" moment is that it is so cross-racial and multi-racial in a new way. I think that a lot of African-American people have luxuriated a little bit in letting some other people do the work, right? Letting some other people carry more of the burden, carry more of the emotional burden and the physical burden of fighting for justice, or sharing the burden a little bit more. I don't know if you're saying any of that, but what you’re saying is leading me in that direction.

MM: Yeah, I have written notes about that too, and it's a come-to-Jesus moment for White America, to realize that what Black people or people of color have been saying for so long is absolutely true and why it took this moment, I do not know. It is amazing to think about in this moment. There's so much to think about at this moment and honestly, that's just what I've been doing. I've really been asking myself, why am I making this work and why do I feel it's important?

Michi Meko, New Plans,Mixed Media On Paper 2017

CH: I want to return to this phrase that you mentioned, "blackening the outdoors." The way you said it, it sounded like a quote. It's not a phrase that I've heard of before, but it's very interesting to me. It makes me think of some of your recent painting work. I feel like your work has prefigured this. So much of what I see is landscape and the maps and what appear to be skyscapes, but through a particular aesthetic lens and using a certain palette, using an array of very black blacks and highlighted with the very white whites. Also, in a metaphorical sense, with your allusion to African-American history and the Black body and these sorts of things. When you say "blackening the outdoors," in a way I feel like you've already been doing that. You were already ahead of that.

MM: Yeah. This is something that I was already interested in, like I said, since 2016, 2017 was where I began to have these thoughts about what it meant to be Black in the wilderness and what does that look like? Are our everyday lives this sort of journey through a wilderness space? Then it's like, what really happens when we insert ourselves absolutely into a wilderness space? Then you have that alone feeling, or the psychological parts that come with inserting yourself into this sort of space. When you think about language, like Americanisms, like this is “public land” or “this land is your land, this land is my land.” Most of this land that a lot of White people sort of go take leisure on is stolen land. I'm really thinking about that and questioning that, but then what happens when we put Black bodies onto that land, and where do we find ourselves in the statistics of park visitors?

It's such a different aesthetic when we think about going to parks, here [in Georgia] versus parks out there [the West]. At least the people that I see through Instagram and all that. They’re like "Oh, we're blackening the outdoors." So they are with their liberal friends, and it looks all cute and they're out in Utah. When you go to, say, the Smokie Mountains and everywhere you see “Trump 2020,” that looks very different psychologically or aesthetically. Once we leave Atlanta, it's not Atlanta.

So, I've been very interested in the aesthetics of the language that people are using out West, versus the language that I've written in my notes or the conversations that I'm having within myself as I read these compare-and-contrast situations or opportunities.

I'm taking this time to absolutely sit in a tent and do these readings, have these sorts of conversations. And it also makes me think about reading Jack Whitten's Notes from the Woodshed. In a way, I've created my own woodshed in this tent to contemplate what it means to be Black outdoors, what it means to have Black leisure. I always think about Derrick Adams' work when I say the words "Black leisure” because he has the figures on the slopes, in the pools. There's this leisure there that we don't always see in a lot of artwork. I think somewhere in there, I was just really tired of telling the same narrative.

CH: What was that narrative?

MM: I think that I'm over the trauma part. I'm wanting to say that there's more to this existence than just this trauma. I'm thinking a lot about that and how can I have these conversations without this conversation about the trauma. I very purposefully chose not to depict that in the work. I'm going to stick to that and I'm going to stick to these thoughts about this idea of leisurely blackness or the time that we've gotten to take. It's almost like there is a moment to breathe and like now, what does the air actually taste like? What has the air actually done? What has the moment of clarity actually done? That's kind of where I'm at right now. A refusal, in a way, to sort of participate in the traditional gallery system or all the pressures that were put on me in the Before Time. That is what led to the anxiety and the mental breaks and all those sort of things. This enormous pressure to perform this artist, “Michi.” I'm just sort of over it.

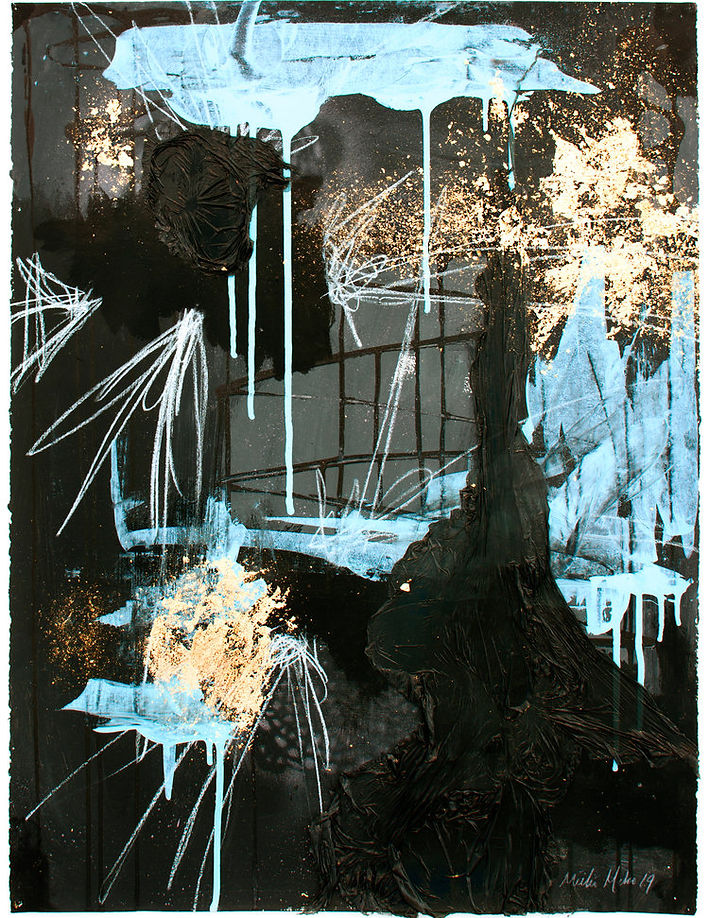

Michi Meko, Storm Warning: 180 Mixed Media 22" x 30"

CH: Well, not to drag you back into it, but when you're tying these ties, you've mentioned it as a meditative practice and do you also, though, see it as a production? Is this something that you see being a physical thing at the end of the process? Or is it really just the practice itself that matters?

MM: Right now it's me proving to myself that I can take these fishing flies. Fly fishing exists as a very white-male setting. It is considered a rich man's sport, given all the things you have to buy. The thing about the fly is that it also considers entomology and all of this stuff. You have to know the long history and what's going on there. For me, my approach is much like my work. I've been making these flies out of old hair weave, potato chip bags, and then old tennis balls, things that I've found, sort of like I've approached my own work.

I'm approaching this fly tying in the same way to see if it’s possible to catch a fish on a hair weave that looks like a bug. It's been real interesting to go out and catch a fish on a hair weave and a feather.

It's still part of the practice. Don't get me wrong, I'm not quitting or giving up. It's just me approaching this leisure or this idea of tying flies very much like I've approached my work in general. The idea of finding things, or not always having to buy things. You can use what you have.

It's still in the tradition of a Lonnie Holley, let's say. In that sort of tradition of making. These [materials] are things that didn't seem important. I'm very interested in that right now, that part of the practice. Using non-traditional materials in a very formal way to go out and catch the fish.

Michi Meko, Haint Windows ,2019 Mixed Media, 22" x30"

CH: When you were speaking about the outdoors and what does it mean for Black bodies to be inhabiting these spaces, I immediately thought of fugitive slaves. I'm sure that's already come to you. In one way I think about becoming a fugitive in wild, uncharted spaces and that being a result of, of course, trauma, and the affliction of trauma as well. If there were a time where you get past the trauma or the trauma just becomes less salient, then coming back to that space, coming back to the wilderness can be done in a much healthier way, can be done in a much more leisurely way, as you've talked about. In some ways, I see you asking what is the conversation after the trauma? And in some ways I see you doing the thing, actually enacting what happens after the trauma.

MM: Since 2017, I’ve taken on this running into these spaces, to be this fugitive, to leave that old life behind. How does one turn off the psychological parts of being alone in a space that has a history of traumas? Woods, dark, night, North Carolina, or the South? How does one continue to put themselves into this space?

My overall goal of this little project in 2017 was to meet a Black male body in a wilderness space, off the beaten path and what would that feel like or what would that look like? What would that be? Could that happen? Could I be somewhere?

The other day, I met this person. His name was actually, Austin Black. His name was Mr. Black so that was kind of interesting, but that moment happened exactly the way I had dreamt it would happen. These two souls, who are going out looking for something, but also at the same time finding something and that was each other, or themselves. He said he looked up and was like, “Whoa, that's a Black dude.” And I told him, I looked up and was like, “That's a Black man's legs.”

It was sort of this great moment that I was able to have, by continuing to go into these spaces, by continuing to push past the what if's and the psychological fears of going into Trumplandia in the mountains and the thought that [something bad] has happened to my people in these mountains or in these spaces. Where does that fearlessness come from?

I’ve begun to realize that what I am talking about is this fearlessness. To purposefully insert oneself into these spaces, like a mountain range, down a ravine, fishing, on a beautiful creek. The scenery is great and it's beautiful and it's all idyllic. It takes a certain amount of fearlessness to insert oneself into these spaces. I'm putting everything together to then reemerge and make this new work that will have these ideas. Like will there be another space like the Black beaches that existed?

That's what the maps [paintings] were all about. They're abstractions and they're contradictions. They're land maps and they're nautical maps and the abstractions that may never get us anywhere. But we still have to continue to have this fearlessness. To continue to go and do, and go and be, to exist. To have life.

Michi Meko is a multidisciplinary artist who lives in Atlanta, Georgia. He received a BFA in Painting from the University of North Alabama.

Instagram @michimeko

Cinqué Hicks is an art critic and writer based in Atlanta, Georgia. He has served as senior contributing editor of the International Review of African American Art, and was the interim editor-in-chief of Art Papers. He was the founding creative director of Atlanta Art Now and co-authorof its landmark volume, Noplaceness: Art in a Post-Urban Landscape. From 2008 to 2012, Hicks was an art critic, arts writer, and columnist for Creative Loafing and has written for a variety of national and international publications including Public Art Review, Art in America, Artforum.com, and Artvoices.