Gabriel Orozco, Black Kites, 1997 ©2009 Gabriel Orozco

Gabriel Orozco

at Tate Modern

By Anna Leung

I enjoyed this show, though admittedly not as much as the first Orozco exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art in the mid-nineties when everything seemed not only fresh and original but poetic and, yes, even beautiful. But the lightness of touch remains, and with it a modesty and an absence of the hectoring in which conceptual artists of his generation often indulge. Not that Orozco is an out-and-out conceptualist artist; in many ways quite the contrary. He rejects the text based documentation that was practiced in the 70s in favour of something more intimate, more somatic that relates to the body as distinct from the mind. He savours concrete reality as opposed to the dream. He is impossible to categorise. He has no fixed medium and till lately no fixed studio. He chose to see himself as a global traveller, a migrant journeying between Mexico City, New York, and Paris, scavenging all the way. His practice is therefore characterised by a multiplicity of positions and practices, methods and mediums. It is possible, however, to discern amidst the photographs, found (and often assisted) objects, drawings and sculptures two main parameters that determine his works: the organic, which is linked to the active body, and the geometric, platonic or abstract that is related to the mechanical. However, and this is important, these are not abstract sets of oppositions but entities that are continually co-existing with one another and touch on an even deeper apprehension, on Orozco’s part, of the blurring of boundaries between art and life. The beauty that I mentioned has its roots in an awareness of life’s evanescence which gives rise to a melding of the poetic and of the concrete. And it is amidst this complex of ideas and feelings that Orozco extracts his findings from the flux of events in life around him.

However, should we choose to see Orozco as a sculptor, as many critics and reviewers do, there are quite a number of historical strands that contextualise his practice and give it a background, notably the Post Minimalism of Eva Hesse in America, Fluxus and Arte Povera in Europe, plus some aspects of Joseph Beuys, though Orozco tends to reject his high-minded seriousness. Orozco strenuously rejected this ‘Sturm und Drang’ school of Neo-Expressionism, fashionable in the eighties, that came to be associated with market forces and was particularly favoured in Mexico when he was studying painting in the art academy in Mexico City, causing him to turn to sculpture or, rather, to whatever was around him and to abandon the studio space for the streets. From this time he began to use the camera, to travel, and to see himself predominantly as a maker who activates reality. Orozco speaks of our acceptance of the real and its accidents when ‘not expecting anything, not being spectators but realisers of accidents, in which reality, when nothing is expected of it, gives us its gifts.’

From this early period comes Recaptured Nature (1991). Made up of one of Orozco’s favourite materials, the vulcanised rubber of abandoned tyres that litter the roads in Mexico City, it features one of his much favoured and much repeated practices, that of turning something inside out. The inner tube has been cut down the middle, welded together with two circular caps from another tyre, and inflated to make a sphere that can theoretically travel in any direction. This work is important primarily because it established a precedent for such works as the famed La DS (1993) and the Elevator in the following year, both of which both involved cutting in order to create a new hybrid, yet familiar and recognisable object: the same but not the same, a theme which is reiterated in the series of photos Until You Find Another Yellow Schwalbe(1995) which we can follow frame by frame in the same gallery. La DS represented the French bid to capture the luxury end of the automobile market from the Americans by producing a feminine as opposed to a masculine design while at the same time insisting on the model’s streamlined futuristic appearance. Of equal importance to the process of cutting is its reconstruction or reconfiguration. Having literally cut out the middle third of the car, Orozco sutured the two remaining halves together, with the result that the car comes to resemble some aerodynamic plane but one paradoxically divested of its engine. A similar transformation overtakes the Elevator. Orozco compares his procedure to that of turning the peel of half an orange inside out, and we begin to sense the degree to which Orozco is fascinated by space as well as gravity. By cutting down to his own height a lift taken from a demolished building in Chicago and relocating it in a gallery setting he creates a strange phenomenon, for its bright gleaming interior and its dark and oil-dirty exterior seem to belong to two different worlds. From the outside, the somewhat squat elevator seems bound by gravity, but on entering what should logically be a confined space there is a sensation of the space being larger inside than out and with it an intimation of ascension, though some viewers experience claustrophobia instead. This is just one of the many conundrums that Orozco plays with.

Gabriel Orozco 2009 © Philippe Migeat

Photography provides many others. Orozco does not use photography as a mode of documentation, but as a record of images which he compares to a shoe box, i.e. a container of ideas that have deeply affected him, and as a means of capturing events that he hopes will continue to have repercussions in the viewer’s mind. What Orozco gives us is primarily a freshness of vision. It is not without significance that most of these images focus on a flux that actually stands in opposition to subjectivity rather than confirming it. This is a celebration of the commonplace that all too often gets overlooked. Many focus on reflections in water, e.g. Pinched Ball, Extension of Reflection, From Roof to Roof, others on the evanescence of a moment e.g. Breath on a Piano, or the parallel universe normally hidden on Showerhead. There is too the astonishing beauty of Sleeping Dog which reveals Orozco’s fascination with the opacity of things, the unknown, unknowable dimension of being. Unlike the Surrealists, he respects rather than attempts to breach this frontier of being.

Many aspects of his work place Orozco in line with Arte Povera, the Italian anti-modernist movement of the late sixties, that was concerned with the ephemeral, the accidental as well as the actual feel for materials and the hand-made. Piero Manzoni was the joker in the Arte Povera pack who sold his breath in balloons, and Orozco often looks back to this critique of the art world. So there is Empty Shoe Box(1993). Empty Shoe Box does not preclude engagement with a savvy viewer; on the contrary, it insists on his/her active ‘disappointment’ for this is after all an old Duchampian joke about art and nothingness. Yet engagement with it e.g. by kicking it or throwing refuse into it (which has happened) would result in the destruction of the object (which has also happened) and needs to be vigilantly guarded against by the gallery personnel – I was told that now there is an alarm built into the shoe box. What we have here is a stalemate. The fact that Orozco explicitly refers to this work as a ‘disappointment’ based on a non-event refers to the public’s appetite for novelty and shock value that is complicit with the art market’s dependence on avant-gardist stratagems and reminds us that not all art need be spectacular – on the contrary, much of Orozco’s work alludes to what lies hidden in the interstices between art and life. But it also places Empty Shoe Box within the realm of play and gamesmanship, a much-favoured area of activity in Orozco’s three- dimensional works as well as in his two-dimensional drawings and paintings. Carambole (1996), a French version of billiards, invites viewers to partake of a rule-free game but with the dramatic addition of a pendulum (Leon Foucault’s*) suspended over the surface of the billiard table - and it is fun. Horses Endlessly Running (1993), a modified chess board four times the normal size, made up of four different colours and manned only by knights, can of course only result in an unplayable, impossible game. Art for Orozco is a serious form of play through which we may, in his words ‘…re-establish or . . . develop contacts, or bridges, in our relationship with reality – the real whatever it is.’

The knight’s move, the only piece, according to Orozco, which by dint of jumping two blocks and then one, ‘is conceived to represent three dimensionality’, came to have a central role in his work, especially in his recent return to painting. On it is based the computer generated series Samurai Tree (2005) which represents the notion of organic growth. The tree in question does not refer to a visual tree but to the conceptual nature of the process that underpins the formation of the image. Central to the artist’s thinking is the idea of starting from the centre and working towards the framing edge while viewing the tree not vertically as landscape but horizontally from above. The tree then becomes a metaphor of growth – as it had been for many pioneers of modernism such as Mondrian and Jean Arp –that spreads in all different directions. Though highly decorative, it is based on a series of delimiting decisions, e.g. to use only circles differentiated by four different colours, red, blue, white and gold (the last of which picks up on his love of icons), to divide each circle into four quadrants, and to use the knight’s move to determine the composition. There is, however, no way of knowing how a painting and its circular motifs will develop. It is the computer that has come up with 677 variants of growth, horizontally and vertically, that Orozco can choose from to make actual paintings. At first he painted these variants of Samurai Tree himself using egg tempera, a very archaic medium. Subsequently using acrylics, he enlisted the help of assistants and friends in Paris and Mexico City. Orozco sees these canvases as diagrams, intellectual games that represent movement and rotation and in which depth is related not to the vanishing point of perspective but to scale. Circles dominate much of his work (Ventilator [1997], Recaptured Nature [1990], Atomist Series.[1996]) and represent a rejection of modernists’ emphasis of the rectangle in favour of a more organicist and somatic approach.

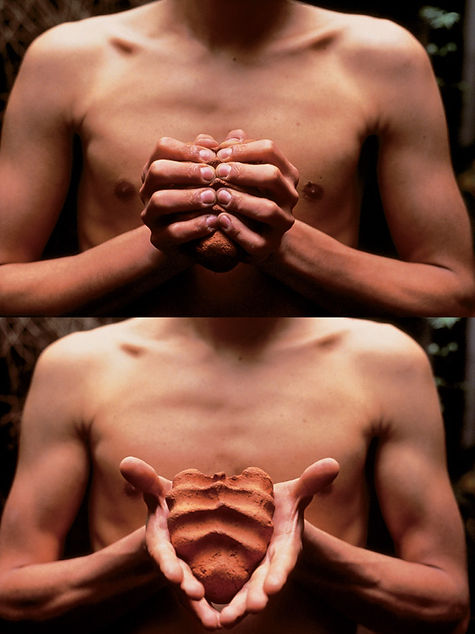

Orozco, My Hands Are My Heart 1991 © 2009 Gabriel Orozco

There are, however, other ways of articulating the body. My Hands are my Heart (1991) is a small, heart-shaped sculpture made by the artist pressing into a lump of brick clay held in his two hands. As the joint photographic image that documents the making of the sculpture seems to confirm this is a gesture that the conjoining of heart and hand translates into an offering – the imprint of his fingers effect a projection of an interior organ. The direct impact of the artist’s body is likewise felt in other works. The pieces making up Pelvis (2007) are made from rolled clay and bear a strong resemblance to body parts, but ones that have variable identities. This is true of much of Orozco’s output, which is wreathed in ambiguity and to some degree inclines towards a cultural practice that that may well have as its aim to escape from any ethnic, nationalistic or primitivist determinism. Yet there is undoubtedly a specifically Mexican accent in Orozco’s referencing of both the culture of ancient Mexico, hearts and skulls, and the debris of modern urban and industrialised Mexico. Chicotes (2010) is made of burst tyres gathered on Mexican highways, another example of finding art forms from within the detritus thrown up by the onslaught of modernity. An aestheticisation of death, it forces us to contemplate the fragility of our fast-paced world. Black Kites (1997), on the other hand, summons up the other Mexico, that of the Day of the Dead. This is simultaneously a drawing and a sculpture or ‘skullpture’ as Orozco quipped. Using a graphite pencil, Orozco has drawn on a human skull to create a web of rectangles that function as a topography, mapping the surface of the cranium which he compares to ‘lines on water, pencil as scalpel.’ Unlike much of Orozco’s work, this took up to six months to complete, a time when the artist was convalescing from a collapsed lung. By way of a response to this meditation on death and in the same room where Black Kites is displayed is a series of prints based on five- or six-worded obituaries selected from the New York Times which lightly revel in a delightful Dadaist sense of humour.

One can immediately sense why Lintels (2001), on the other hand, is associated with death and mourning. These fragile and limp rectangles of grey lint, made out of human and other detritus that collect in the filters of tumble dryers, have been hung out as on washing lines high above our heads so that as we walk towards the exit of the exhibition we have to walk beneath them. Coincidently the first installation took place in a New York shocked to the core by the September 11 attack; Lintels therefore could not but function as a specific memento mori. But even in the absence of a national catastrophe the work addresses the essential transience of our day to day lives. In ethos it is close to the Cagean tradition, celebrating through the randomness and precariousness of things a means of avoiding the despotic supremacy of the self and in this way reconnecting with reality.

Despite the many referencings to death and temporality this is on the whole an even tempered and well-mannered show. Orozco keeps his distance and only very seldom implicates himself. His work is not about himself but about the variables and permutations within the realm of our realities. He is basically a pattern maker; his intelligence enables him to wrest aesthetic form from chaos. His work lifts the spirits without being in any way religious. It is on the whole affectionate and manageable, helping us to see in the outside world beyond the gallery what he had taught us to see from within the manifold parameters of his art work.

© Anna Leung, 2011

* invented in 1851 to demonstrate the earth’s rotation

All quotations from Yves Alain Bois (editor), Gabriel Orozco, October Files, 2009

Anna Leung is a London-based artist and educator now semi-retired from teaching at Birkbeck College but taking occasional informal groups to current art exhibitions.