Elizabeth Bradfield, Photo by Lisa Sette

Eco-Intimacy: An Interview with Elizabeth Bradfield

A Dialogue with Dawn Skorczewski

Toward Antarctica: An Exploration, Boreal Books/Red Hen Press, 2019

Once Removed: Poems, Persea Books, 2015

I met Elizabeth Bradfield, Co-Director of the Creative Writing Program at Brandeis University, in 2017 when we organized an event to celebrate Alicia Ostriker, whose poetry, teaching, and criticism fostered generations of poets and scholars. This past fall, Liz and I created a celebration of the life and poetry of Anne Sexton at Brandeis, fifty years after her death. Bradfield has achieved national and international recognition as a poet and naturalist who founded and edits Broadsided, a digital journal that publishes original collaborations between writers and visual artists. She has also worked as an expedition guide in the Arctic and Antarctic, led whale watches, and assisted in research projects on marine mammals as a field biologist. She won the Audre Lorde Award in Lesbian Poetry for her first book, Interpretive Work; a Pacific Northwest Book Award and other honors for Cascadia Field Guide: Art, Ecology, Poetry, a ground-breaking “feel guide” engaging the bioregion of Cascadia that she co-created with Derek Sheffield and CMarie Fuhrman; a Stegner Fellowship at Stanford University; and a Massachusetts Cultural Council Individual Artist Award. SOFAR: Poems, her fifth book of poetry, will be published in August of 2025.

Dawn Skorczewski: You’re a poet, naturalist, editor, teacher, theorist, and activist. You work across so many disciplines, and even, I would argue, across space and time, to create what I think of as an aesthetics of eco-intimacy. As I look over the trajectory of your stunning career, I see a few moments as key to your development as a poet and environmental activist. But what do you think? How do you think about your journey to this moment?

Elizabeth Bradford: Eco-intimacy––I love that term! I’m going to use it from now on. I’m not sure I’d call myself a theorist or activist, but yes, the other things are true (I’ve also worked as a caterer, deckhand, and web designer, which, although less thematic, also built my sense of the world and myself in it). I do hope that I can use all the disparate corners of my work and life to help us connect and better see ourselves in relation to the more-than-human world.

I don’t think of myself as an activist, because I am not often directly engaged in campaigns or conversations with legislators; you’ll more often find me with a camera and data sheet than a protest sign, but I’m so grateful to all the powerful speakers and advocates who do public work for the beings and places and people I care about. But I know that politics is not my strength; I put my energy into field work, education, and writing, all of which sustain me and, hopefully, help buoy and sustain those who are able to lobby, march and protest in impactful places and ways, and work toward social and legislative change.

SOFAR: Poems, Persea Books (forthcoming, August 2025

Interpretive Work: Poems, Arktoi Books/Red Hen Press, 2008

DS: Starting with your very first book, Interpretive Work, you made a commitment to witnessing many kinds of experiences. But you do so in a language that is beautiful; we might even say exquisite. Can you say a little bit about how you find the images that animate your poems?

EB: I think that one of the most important things I can do as a poet is to listen to other humans and other beings, to the events we find ourselves alongside or within. And I don’t mean to just witness the surface details but really attend to how experiences resonate with personal and global histories. My favorite way to find a poem is to suddenly notice myself reacting to something with surprise tinged by a hint of judgment––moments where my inner voice is asking, “What the fuck?” I like those moments, because when I really stop and attend them, they reveal not just the ridiculousness of the world around me, but my own culpability in those moments. They reveal the lenses through which we see the world, and, for me, writing poems is a way of making those lenses clear to myself.

As for the images themselves, I suppose that poets like Anne Sexton are my influences, poets who bring a new image-world, different from the poem’s, into their metaphors. For example, in Interpretive Work, there’s a poem in which I describe dandelions along a trail as looking like airplane aisle lights. The poem, “Nonnative Invasive,” is about our human impact on the places we love, and the image allowed me to bring an urban/industrial sense to a mountain trail. And isn’t that just what they look like? It tickles me that the image is a little funny, too. I love an image that can make me snort––in surprise and delight––when I come upon it.

Theorem (in collaboration with artist Antonia Contro), Candor Arts, 2019 & Poetry, Northwest Editions, 2020

DS: What is your favorite Elizabeth Bradfield poem?

EB: Oh gosh. It depends on the circumstance! There are poems that I know work well at public readings, that are easier to connect to because of their humor and wordplay, and I like the sly work they do. But there are also poems of mine that are quiet, tender, and vulnerable. Simple, even––I think those are the ones I might hold most dear, because they have stepped away from intellectual bluster to lay bare, for lack of a better term, the soul. But it seems to me you can’t have one without the other. Each type of poem–poems that play hard with language and sound, that intellectually query history or historic figures, that relate an exceptional encounter, or that sing in a more lyric “cri de coeur”--they all make up a poetic ecosystem. Each depends on the other, grows from and with the other, has their own need for light and nutrients, their specific niche in which they flourish, their needs for shade or protection or their ability to withstand extreme conditions.

DS: I loved the Brandeis podcast I heard you on, where you talked about teaching students who love to write, playing the clarinet, diving to the depths of the ocean, and bringing poets back from the dead to read at the university. If you had to pick ten poets to bring back from the dead, and each can read one poem, who would they be, and what would they read? Please feel free to make an actual list.

EB: I love lists! First, I want to bring back Elizabeth Bishop, and I want to hear her read “The Imaginary Iceberg.” I think of that poem every time I see ice at sea, and I’d love to talk to her about its origin. I’d ask Anne Sexton to come back and read some of her nature poems (she’s such a great nature poet!), maybe “Lobster,” if I have to pick one. Her humor and exacting, surprising images are such a delight. Sappho, of course, just because I’m so curious to know what a poet so steeped in legend and so beloved and exemplified and iconified would actually be like. Whitman, for the spectacle (who knows what he’d do?). I want to hear him read “Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking” and I think I’d like to see him work a room. Alan Dugan, cranky grump and tender soul that he is. Could I have him read “Love Song, I and Thou” to Philip Larkin, who would respond with a poem of his own? This is getting fun. Audre Lorde, for sure, alongside Adrienne Rich. I’d like to listen to the two of them talk, love on each other, butt heads, and thereby help us all write fiercer. Even though she’s not a poet, I’d like to bring back Toni Morrison and have her read Playing in the Dark. Can I bring back my friend Eva Saulitis, please? She died too young, and I’d love to hear her read anything, but maybe her “Prayer 46” from Prayer in Wind most of all. Finally, whoever the Beowulf poet is, I want to tell them that it’s my favorite poem. I want to hear how the words sound coming from a body from the time it was written.

Cascadia Field Guide: Art, Ecology, Poetry, with CMarie Fuhrman and Derek Sheffield, Mountaineers Books, 2023

Broadsided Press: Fifteen Years of Poetic and Artistic Collaboration, 2005 – 2020, editor, with Miller Oberman and Alexandra Teague, Provincetown Arts Press, 2022

DS: Your forthcoming book, SOFAR: Poems, begins with a collection of epigraphs from marine biology to poetry to nonfiction to philosophy. The epigraphs ask us to think of these poems through many lenses at once. Do you see these frames as essential to our understanding of how this poetry works and where it is situated, or are they a little “song” at the start?

EB: I love epigraphs, indexes, notes, and other ephemera. I suppose, to answer your question, the epigraphs in SOFAR are both information and song. I mean, aren’t they beautiful? My partner has always said, “You’re only as famous as your sources are obscure,” a quote that she misquotes from someone…. We’re not sure who. Which cracks me up, given the quote. But I think literary ancestry is important. And I absolutely feel in conversation with the ideas and words of others; having them present in the book is a way of acknowledging their influence.

DS: Many poems in SOFAR evoke the deep ocean and nautical life in relation to the body. Has your thinking about the ocean changed as the threat of climate catastrophe becomes quotidian?

EB: Is it quotidian? I suppose it is a daily awareness, so yes, it is quotidian. Even writing that makes me so sad. But all the same, the way that “symptoms” of climate change keep appearing feels ever new. Most recently, the die-off of Gray Whales in the North Pacific was tied to reduced sea ice in the Bering Sea that resulted in reduced invertebrate productivity, and thus the whales’ starvation. That was a tough blow. Particularly given that Gray Whales had done such a good job of recovering from the trauma and legacy of commercial whaling. It does seem like there’s always a new heartbreak, a source of fresh sorrow that makes the crisis seem anything but quotidian. For me, the ocean has always been a place of wonder and solace. But as is true of any place you build a relationship with, more love brings more attention brings more awareness of both beauty and change. More love leads to more knowledge leads to more appreciation, but also to an increased sensitivity to disruptions and moments when things seem awry.

DS: I appreciate how you refined the question. How has your awareness of the effects of climate change influenced your thinking and writing?

EB: This morning, I headed out early to walk a forest path and look for migratory warblers, it being prime season for that. The trail circles a pond and is a favorite of many people. The place is called “Beech Forest,” named for the beautiful American Beech trees that shade much of the trail. Today, there was heartbreak on the walk because so many of the Beech trees showed sign of wasting, their leaves curled in on themselves. They are going to die. I wrote a poem, “At the Smallpox Cemetery, Provincetown” that is in SOFAR that engages this particular grief, connecting it to human diseases that have occupied this same place. I feel, deeply and personally, the sorrow of losing those trees, and I want to find an expression for that feeling, because I think it’s one that many of us share.

Yesterday I was at a training for my volunteer work at the Cape Cod National Seashore as part of the Seal Education Team, and Dr. Wendy Puryear shared an update on her research regarding Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza, which might not be directly related to changes in our climate. But watching a new virus move around the world, developing and evolving its pathways through populations, and its increasingly integrated presence in all of our lives, human and more-than-human, I suppose I was struck anew by how dynamic and interrelated the world is, often in surprising ways. Every bird, virus, seal, flower, human, and shoreline are in motion, responsive to such a complicated set of stimuli that we could never tease them apart. Nor should we, in many regards. I think that, if anything, I become increasingly aware of how dangerous it is to consider one issue at a time in isolation, be it disease, population migration, shipping activity, or sea level rise. They all connect and influence each other. All of this also makes me painfully aware of the gaps in our knowledge of some basic life histories of beings in the ocean, and that I’ve spent much of my life learning about marine life and ecology, and the more I learn, the more I can see how little we know. That’s both exciting and terrifying. Exciting, because there are ways we can contribute still to a developing body of knowledge. Terrifying because the time for getting “baseline data” on how the marine ecosystem operates without a heavy human footprint is long in the past. We don’t fully know what we’ve lost, what’s changed, or what “normal” might be. I have been lucky to have had a privileged view of the ocean leads me to want to share and help others feel the connection I do, to pull back the curtain on some of the mystery which, of course, if we look closer, only leads to more wonder, more mystery. As Denise Levertov says, “Accuracy is the gateway to mystery.”

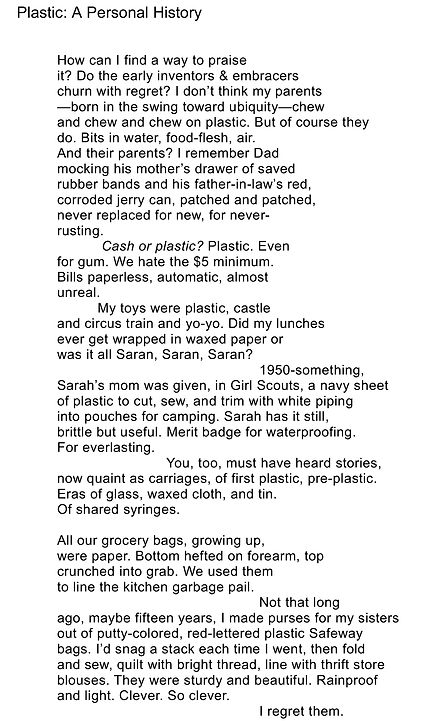

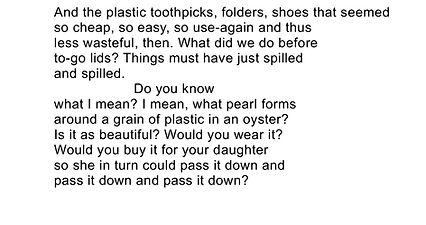

DS: Of all the poems in your new collection, I am most tempted to teach “Plastic: A Personal History.” It starts off with the question, “How can I find a way to praise/it?” But it ends with a question about legacy. For me this poem plays with a paradox: that plastic is toxic, ubiquitous, destructive AND that it is a part of our lives. I love how the poem ends with a series of questions, because it suggests our participation in the forging of generations of plastic. The image of the speaker making bags for her sisters is also moving. For me this poem exemplifies the poetics of eco-intimacy I mentioned earlier. I read the final lines as saying “will you resist?” “Can you decide to change this terrible tradition?” Do you see this poem as an example of a desire to witness and critique?

EB: Well, thank you! This poem has surprised me in how widely it has traveled. I thought of it as a snarky, playful poem when I wrote it––light, even––but it has hit a chord, and I can understand why. Like many of us, I feel exasperated and defeated by the presence of plastic in my life. It seems inescapable. I wanted to look back and consider how we got to this moment … to think about the time when plastic seemed like a wondrous, new, clean, life-enhancing product with fairly benign side effects (more trash, sure, but in the form of roadside litter that could be picked up and removed). And to acknowledge the benefit of plastic in our lives (such as in medical equipment, like hypodermic needles). For me, I think the ending asks us to reckon with what is, in truth, our legacy at this point.

Approaching Ice: Poems, Persea Books, 2010

This Assignment is So Gay: lgbtiq poets on the art of teaching, Sibling Rivalry Press, 2013

Edited by Megan Volpert

Photo from Toward Antarctica: An Exploration by Elizabeth Bradfield (Boreal Books, 2019)

DS: In a recent interview, you remarked on your interest in words and images “amplifying” each other. You say words and images “create energy.” I think that comment was also about your work with the sculptor Janice Redman, whose studio you often write in and whose oar sculpture is part of SOFAR’s cover image. Can you say a bit more about collaboration and creativity?

EB: Yes! I think I was speaking about broadsides and hybrid work that incorporate both actual visual images and text, not so much images in the sense of literary metaphors. But I do think that sound and image create energy––both when it’s words in a poem and when it’s words + art. My longstanding friendship with Janice Redman, who is my neighbor and a brilliant sculptor, has been an animating force behind my writing. We try to work together one day a week, most often in her studio as I’m much more portable than she is. We’ll set a timer for 30-40 minutes, work, chat and stretch for 2-5 minutes, then go back to it. This kind of partnership and “parallel play” helps both of us; on my end, it helps me face the page when I’m feeling daunted. Watching Janice go through the ups and downs of her creative process helps me weather my own––the successes and the flops we have to recover from, the grind of it and the joy of making. Janice and I have directly collaborated on a few projects, most recently making the cover image for SOFAR, and before that the film “Personal Flotation Device”. I’ve written a few poems in response to her visual art, and I’ve been lucky to have had other collaborations in my life, from working on Broadsided to making Theorem with the artist Antonia Contro, to creating Cascadia Field Guide with Derek Sheffield and CMarie Fuhrman. None of those projects would have had the form they have without the conversations and wranglings––sometimes painful and difficult, sometimes joyous and brilliantly obvious––that went into their making. True collaboration is a vulnerable, difficult process, but also one that can be so wildly rewarding in all sorts of unexpected ways. I learn something new from each one, and I hope there are many more collaborations in my future.

DS: I haven’t yet remarked on my favorite poems in your new volume, which are about desire. Here I feel your themes of listening, living in nature, and making meanings all converge in such gorgeous poetry. For example, “Kiss me like a limpkin.” How do you think about the place of desire in your poetry?

EB: Desire and the body are so much a part of my relationship with the world. What is more intimate than desire? I’ve experienced embodied surges in response to particular rocks, landscapes, and encounters with the more-than-human world–––the thrill of wonder and the spark of desire are not that far distant from each other. Maybe that’s because, when I’m open to wonder or awe or sorrow, I’m porous in other ways, too. This comes back to eco-intimacy in another way, doesn’t it? And I think part and parcel of that desire, it is important to note, is queerness. This is an eco-queer book, shifting presumed intimacies in all kinds of ways. Poems engaging the body, a decades-long relationship between two women, and also how menopause and time can shift both are embedded everywhere in the book and are the emotional foundation from which so much of it grows.

DS: A few years ago, I had the exhilarating experience of being on a whale watch in Cape Cod, and YOU were the naturalist narrating the trip. We saw more than a dozen whales that day; many were close to the boat. I learned so much from hearing you talk about them. At the end of the trip, you said “this has been an embarrassment of riches!” Your allusion to Simon Schama’s book An Embarrassment of Riches seemed so apt to me, given our tendency to romanticize or colonize nature. But at the same time, of course, you were talking about something that was quite true––we had been oohing and ahhing at A LOT of whales! I see this combination of awe and skepticism throughout your work. Am I wrong to think that you identify the ocean as a colonized space even as you ask us to witness the breathtaking beauty of the natural world?

EB: Wasn’t that a day?! The generosity of the marine ecosystem around Cape Cod continually astounds me. As for my ambivalent feelings about “selling” the experience of encountering wildlife, you have caught me out––awe and skepticism is a great description of my own inner tensions, which are an extension of what I was trying to describe in my answer to your question about “Plastic: A Personal History.” I do feel awe still at the wonder and privilege of going out to spend time with whales, even though I’ve been doing this in various forms since 1994. I also want to make sure that awe isn’t glossing over some reality we should be interrogating or acknowledging. I view the ocean less as a colonized space than an industrialized space, though both are true. The primary lens through which governments view the ocean is that of use: fisheries, shipping, “ecosystem services”, energy (whether oil, gas, or wind). I think often about what a “clean” surface the ocean presents––a glossy, reflecting lid of water. Even studded with fishing gear and littered with floating balloons, the sheer volume of the water itself is hard to reckon with. And then what lies beneath that surface? How can we understand the lives of beings that have cycles and senses and histories so different from our own?

Liz at work as a naturalist on the Dolphin Fleet whale watch, Provincetown, MA

DS: You are the new director of the Poetry Concentration in the Low-Residency MFA program at Western Colorado University. Congratulations!! What takes you to the west?

EB: Yes! I just started this new job in May, so I’m still wrapping my brain around it, but I’m so excited to be part of the community at Western Colorado. Part of the thrill is to work with graduate students again––writers who are taking another step on their path, dedicating themselves seriously to an artform that will reward them deeply (though not necessarily financially). I love working with undergraduates, and my students at Brandeis University have taught me so much, so it’s less a turning away than a shift. I’m also eager to move some of my working life westward toward the places nearer those I grew up, and where my sisters and parents still live. I can’t imagine leaving Cape Cod, and I’m grateful that the job is remote except for the summer residency in Colorado. I’m also eager to build a life that helps me nurture my connection to the west.

Elizabeth Bradfield’s books are SOFAR: Poems (forthcoming in August), which includes poems that were published in The Atlantic Monthly, The Sun, and Orion; Toward Antarctica; Once Removed; Approaching Ice, which was a finalist from the James Laughlin award from the Academy of American Poets; Interpretive Work, which won the Audre Lorde Prize in Lesbian Poetry; and the anthologies Cascadia Field Guide: Art, Ecology, Poetry, co-created with CMarie Fuhrman and Derek Sheffield and winner of the 2024 Pacific Northwest Book Award; Broadsided Press: Fifteen Years of Poetic/Artistic Collaboration, co-created with Alexandra Teague and Miller Oberman; and Theorem, with artist Antonia Contro. Her poems have appeared in The Slowdown, The New Yorker, Poetry and her honors include a Stegner Fellowship. Liz works as a naturalist and field assistant at home on Cape Cod, teaches creative writing at Brandeis University, and is Editor-in Chief of Broadsided. https://ebradfield.com/

Elizabeth Bradfield

Dawn Skorczewski is Professor of English emerita at Brandeis University and Senior Lecturer at the University of Amsterdam. Her most recent book is Sieg Maandag: Life and Art in the Aftermath of Bergen-Belsen (2020). Forthcoming books include The Happiness Reader (2027), and The Art of Invisibility (2027).

Dawn Skorczewski